When most people think about fire safety, they picture alarms blaring or sprinklers drenching a room. That’s active fire protection. But there’s a quieter hero at work too: passive fire protection.

Passive fire protection (PFP) is baked right into a building’s structure. We’re talking fire-rated walls, floors, doors, sealants and coatings, all designed to slow the spread of fire and smoke. Instead of attacking flames directly, PFP gives people more time to escape and helps keep buildings standing long enough for firefighters to do their job.

Think of it like the seatbelt in your car. You don’t notice it most days, but in a crisis, it can be the difference between life and death.

In this guide, we’ll cover what passive fire protection really is, the main types, why it matters, and how to keep systems compliant.

Let’s clear this up right away: passive fire protection isn’t about sitting back and doing nothing. The “passive” part just means these systems don’t need you to push a button, pull a lever, or wait for sensors to trigger. They’re built into the very bones of a building.

In plain English: PFP is the set of design features and materials that stop fire and smoke from spreading.

Instead of spraying water or releasing gas (that’s the “active” team), PFP holds fire in its tracks – slowing it down, containing it, and keeping escape routes usable.

Here’s a simple way to think about it:

Both are essential, but PFP does its job silently, 24/7, whether there’s a fire or not.

You’ve probably walked past passive fire protection without even noticing:

These don’t scream “safety feature”; they just blend into the background. Until, of course, they’re needed.

Here’s the big deal: PFP buys time – and in fire safety, time is everything.

Without PFP, even the best sprinkler or alarm system might not be enough.

Passive fire protection doesn’t get the spotlight. There are no dramatic water sprays or loud sirens – just walls, coatings and doors quietly doing their job. But here’s why it’s such a big deal:

When a fire breaks out, seconds matter. Smoke can fill a room in less than a minute, and flames can double in size every 30 seconds. PFP systems like fire-rated doors and compartment walls hold back fire and smoke, creating safe paths for evacuation. That extra 5–10 minutes can mean the difference between everyone making it out safely and tragedy.

It’s not just about people (though they always come first). Businesses have expensive assets, eg servers, medical equipment, machinery, documents. By containing a fire to one section of a building, PFP helps limit damage and reduce downtime. Instead of losing an entire facility, damage may be confined to a single room.

Steel weakens dramatically in high heat; at around 1,100°F (593°C), it loses about half its strength. Passive fireproofing materials like intumescent coatings or spray-applied fire-resistant materials (SFRM) insulate steel so that structures don’t collapse prematurely. This isn’t just about saving buildings; it’s about giving firefighters a stable structure to work in.

Authorities don’t leave fire safety up to chance. In the US, the International Building Code (IBC) and NFPA standards mandate passive fire protection features. In Europe, EN standards require fire resistance ratings for walls, doors and claddings. If your building isn’t compliant, you’re not only risking safety; you could face fines, shutdowns or legal liability.

Insurance companies love buildings with proper PFP because they know the risks are lower. Strong compartmentation and fireproofing reduce the chance of total loss. That can translate into lower premiums or at least fewer arguments if you ever need to make a claim.

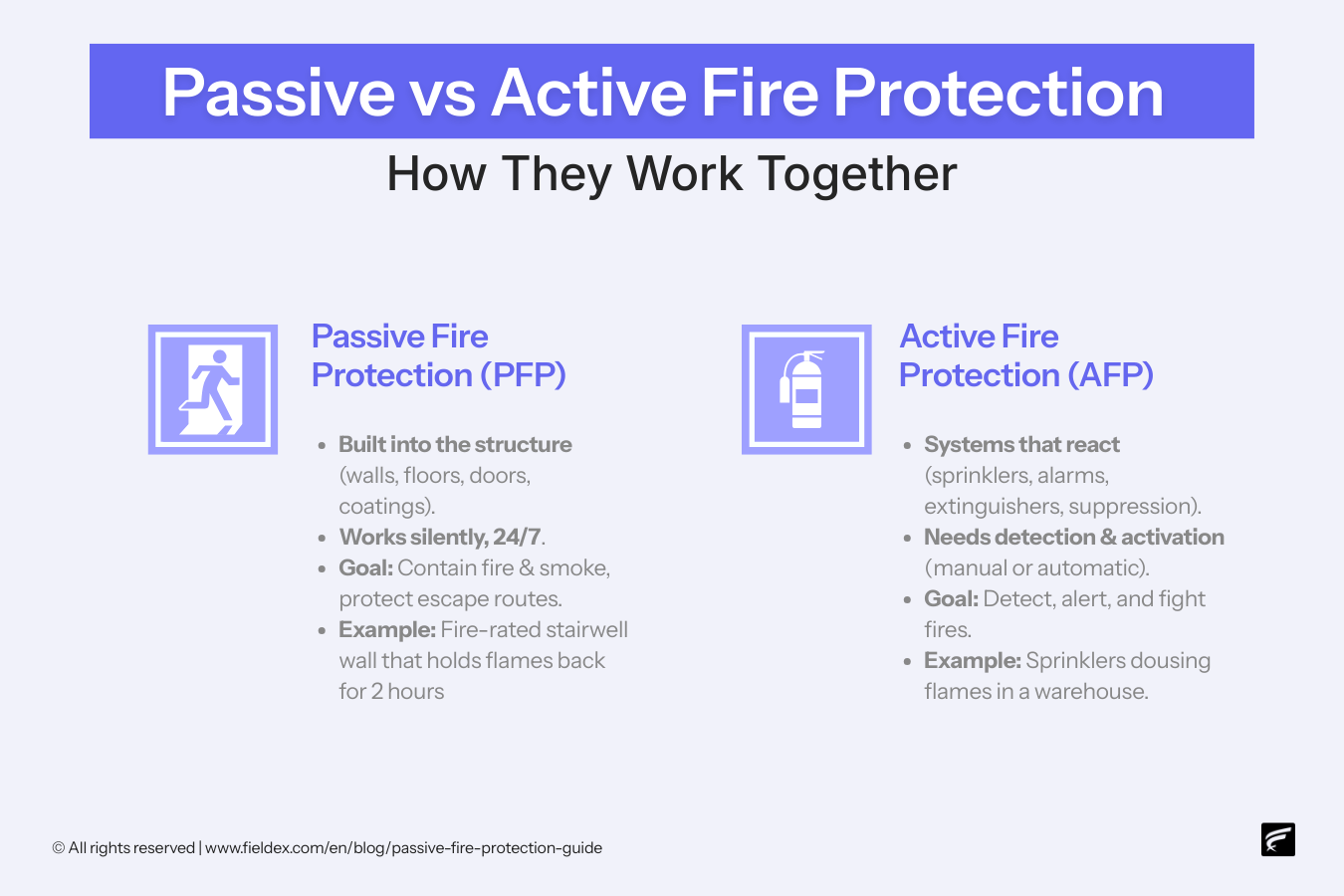

Passive and active fire protection work best together. Active systems (sprinklers, alarms, extinguishers) fight the fire head-on. Passive systems hold the line, slow the spread, and buy time. One without the other leaves gaps in your safety net.

In short: Passive fire protection matters because it buys time, saves lives, reduces costs, and keeps buildings safe. Without it, even the most advanced sprinkler or alarm system could be fighting a losing battle.

Passive fire protection comes in many forms. Some are obvious, like those heavy fire doors you’ve probably seen in stairwells. Others are practically invisible, hidden in walls, ceilings or wrapped around beams. Together, they form a layered defense that slows fire down and keeps people safe. Let’s walk through the key types.

These are the backbone of passive fire protection. By dividing a building into “compartments”, fire-resistant walls and floors prevent flames and smoke from moving freely from one area to another.

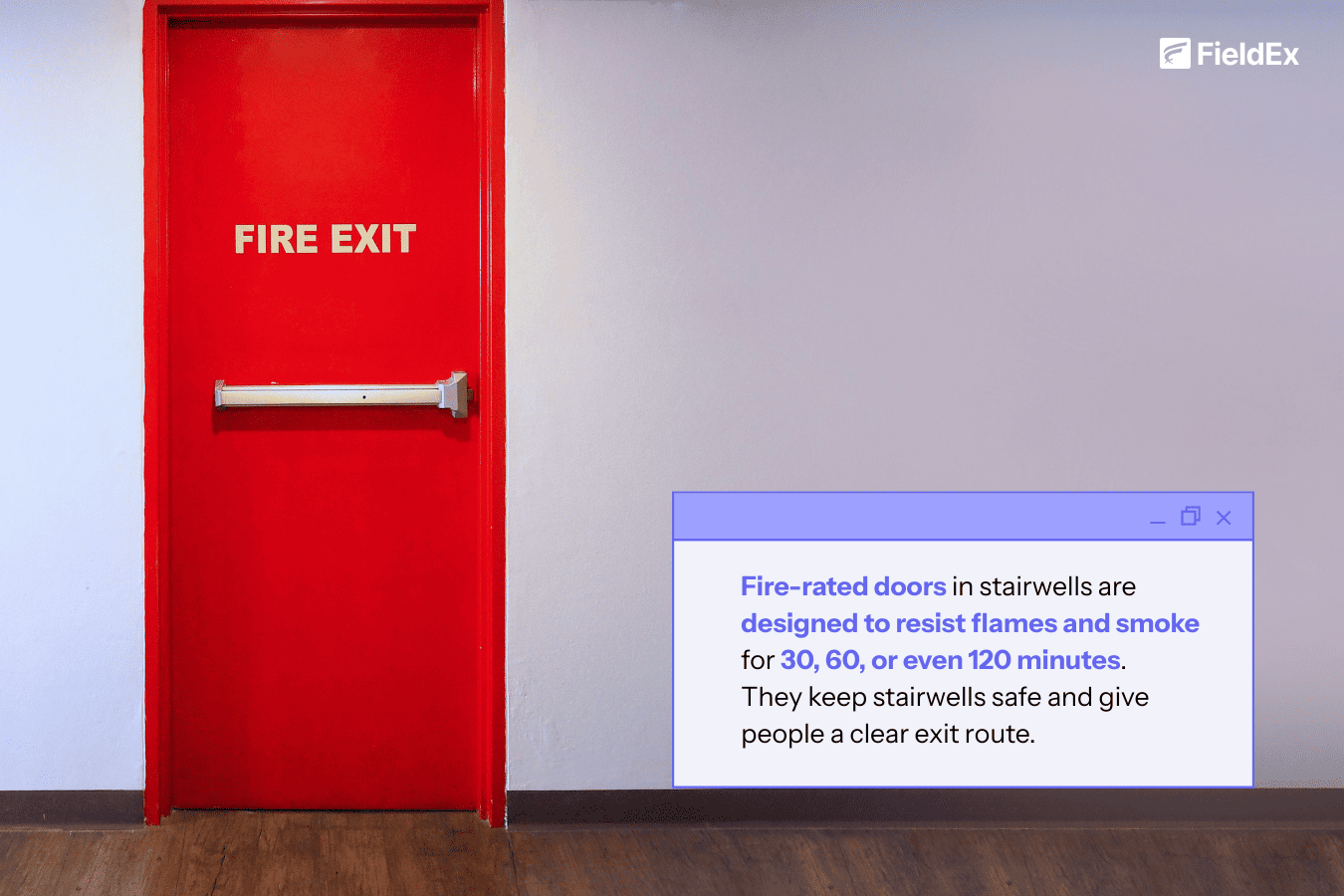

Not all doors are created equal. Fire-rated doors are engineered to resist flames and smoke, and they’re usually paired with special hardware like self-closing hinges and smoke seals.

Common mistake: Propping open fire doors with wedges. It might feel convenient, but it completely defeats the purpose.

Ever noticed cables, pipes or ducts running through walls? Those little gaps can be highways for fire and smoke. That’s where firestopping systems come in.

Steel is strong – until it gets hot. In a fire, it can buckle and collapse in minutes. Fireproofing keeps it cool.

Sometimes, smoke is more dangerous than fire itself – it’s fast-moving, toxic and disorienting. Smoke barriers and curtains guide smoke movement to keep escape routes clear.

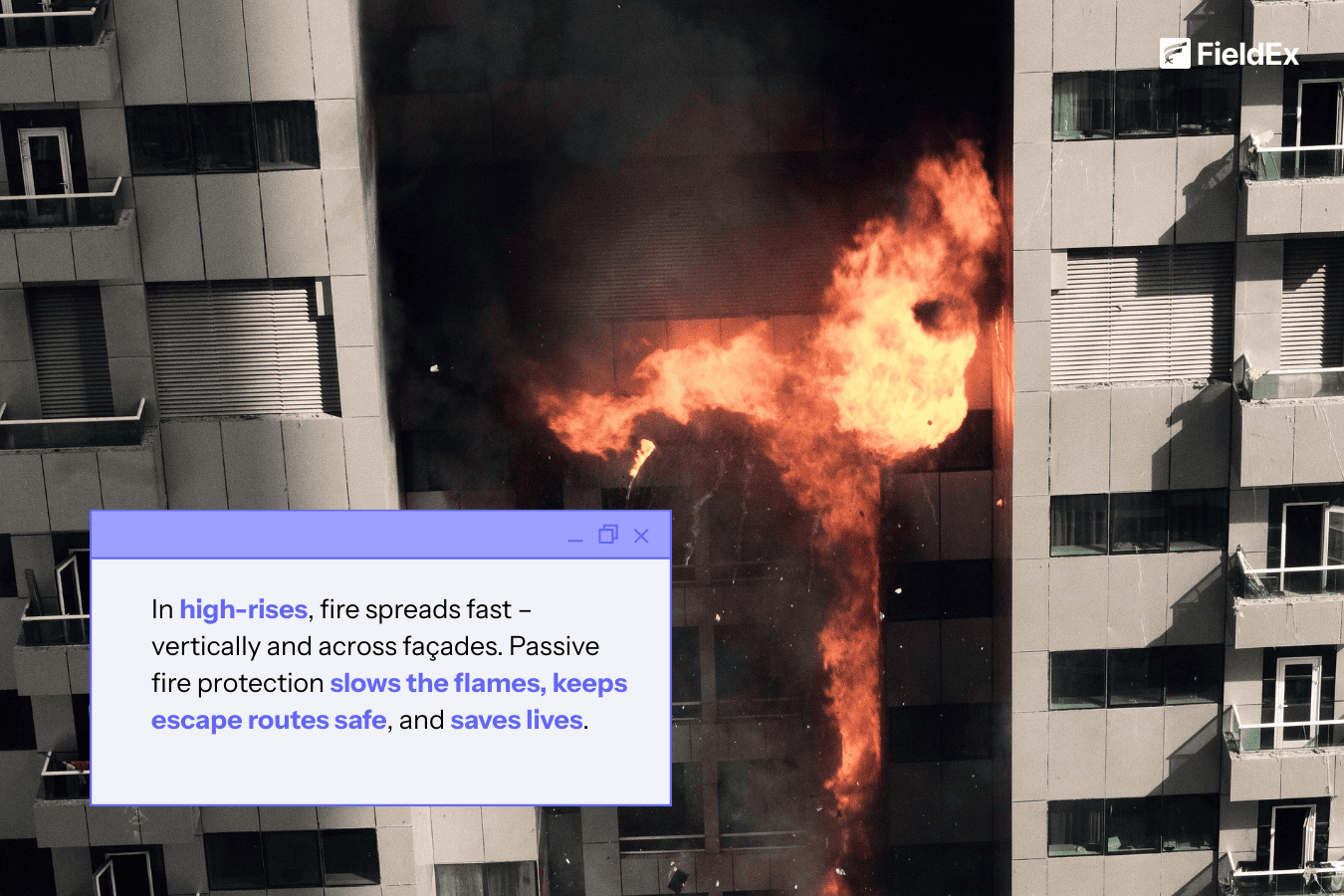

After incidents like the Grenfell Tower fire in London, the spotlight has been on safe exterior cladding. The wrong materials can fuel flames; the right ones can help stop them.

Takeaway: Each type of passive fire protection plays a unique role. Together, they form a layered safety net – like a chessboard of defenses – that keeps fire from spreading uncontrollably.

Here’s where a lot of people get confused. Fire protection isn’t an either/or choice between passive and active measures. They’re two sides of the same coin, and the safest buildings always use both.

Think of it this way:

Would you drive with just one of those? Exactly. The same logic applies to fire safety.

When passive and active fire protection work together, you get:

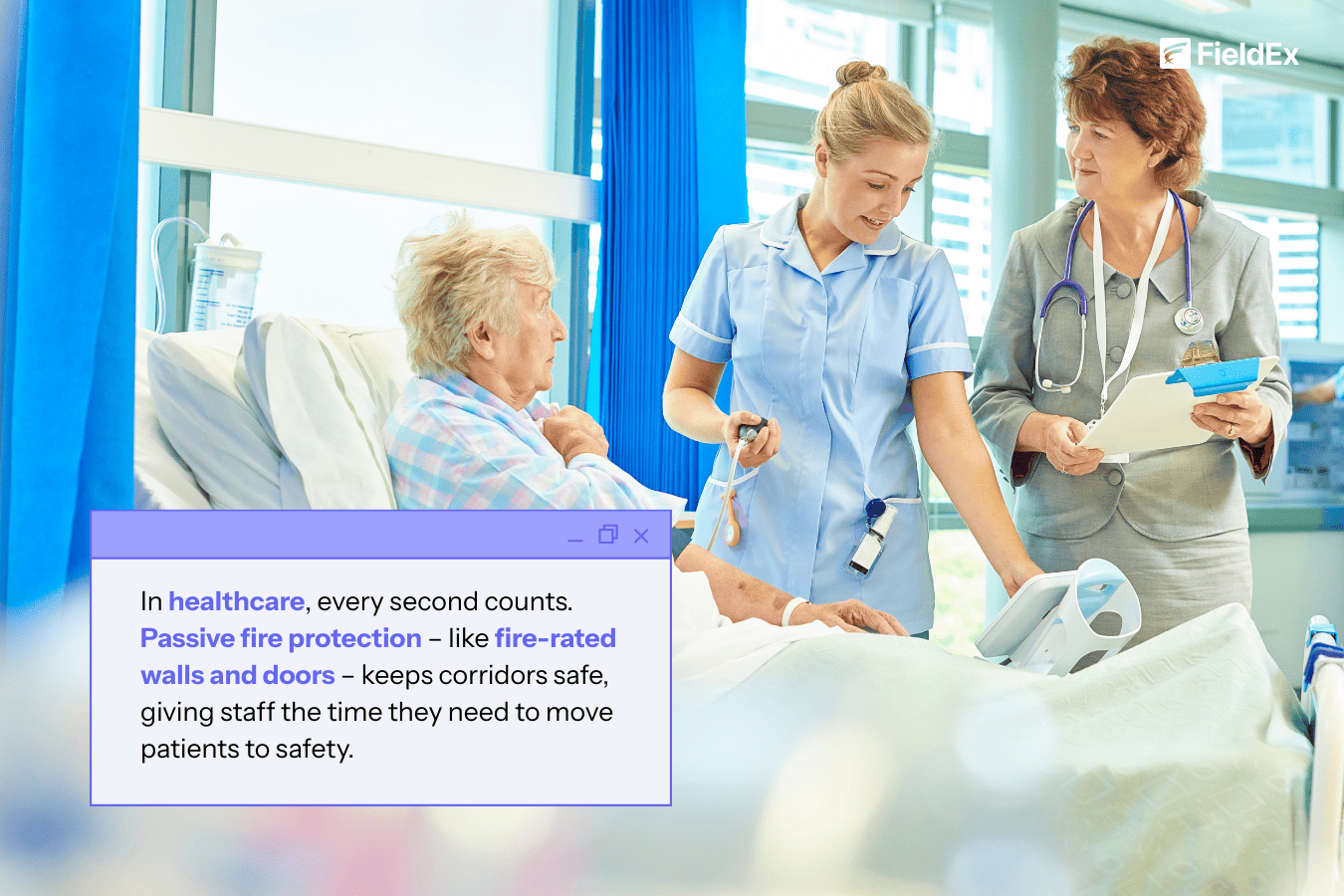

In healthcare, every second counts. Passive fire protection – like fire-rated walls and doors – keeps corridors safe, giving staff the time they need to move patients to safety.

Designing passive fire protection (PFP) isn’t just about slapping some fireproof paint on steel beams and calling it a day. It requires planning, knowledge of fire codes, and an understanding of how different building types behave in a fire. Here are the main factors to keep in mind:

Every region has its own rulebook:

Skipping code compliance isn’t just unsafe; it can lead to fines, lawsuits or even demolition orders.

You’ll often see walls, doors or coatings described as having a 30-minute, 60-minute or 120-minute rating. This doesn’t mean they “fail” after that time; it means they’ve been tested to withstand direct fire exposure for that long while maintaining structural integrity.

The higher the risk, the higher the rating you’ll need.

The use of a building heavily influences PFP design:

A key principle of PFP is dividing a building into fire compartments. Each compartment is like a box that contains a fire for a set time, stopping it from spreading freely. This strategy protects evacuation routes and keeps fires manageable.

Not all fireproofing materials are created equal. Choosing the right one depends on the structure:

PFP should never be designed in isolation. Sprinklers, alarms and suppression systems need to work hand-in-hand with compartmentation, fire doors and coatings. A holistic design makes sure there are no weak points.

Bottom line: Designing passive fire protection isn’t just a box-ticking exercise. It’s about understanding fire behavior, the people inside the building, and the risks tied to different structures. Get the design right, and you’re building resilience into the walls themselves.

Passive fire protection is only effective if it’s done right. Unfortunately, there are a handful of mistakes that keep popping up on inspections – and they can turn carefully designed systems into little more than expensive decoration.

Here are the big ones to watch for:

Not all drywall, sealants or coatings are fire-rated. Cutting corners with cheaper, non-certified products might save money up front, but in a fire, they’ll fail almost instantly. Fire safety materials go through rigorous testing for a reason.

A gap sealed with the wrong caulk is basically a chimney waiting to happen. Firestopping needs to be applied correctly, with tested systems that match the exact type of penetration (pipe, cable, duct). One sloppy job can compromise an entire compartment.

This is a classic. Fire doors are designed to stop flames and smoke – but only if they’re closed. Wedge them open with a brick or prop them with a chair, and they become regular doors again, letting fire spread freely.

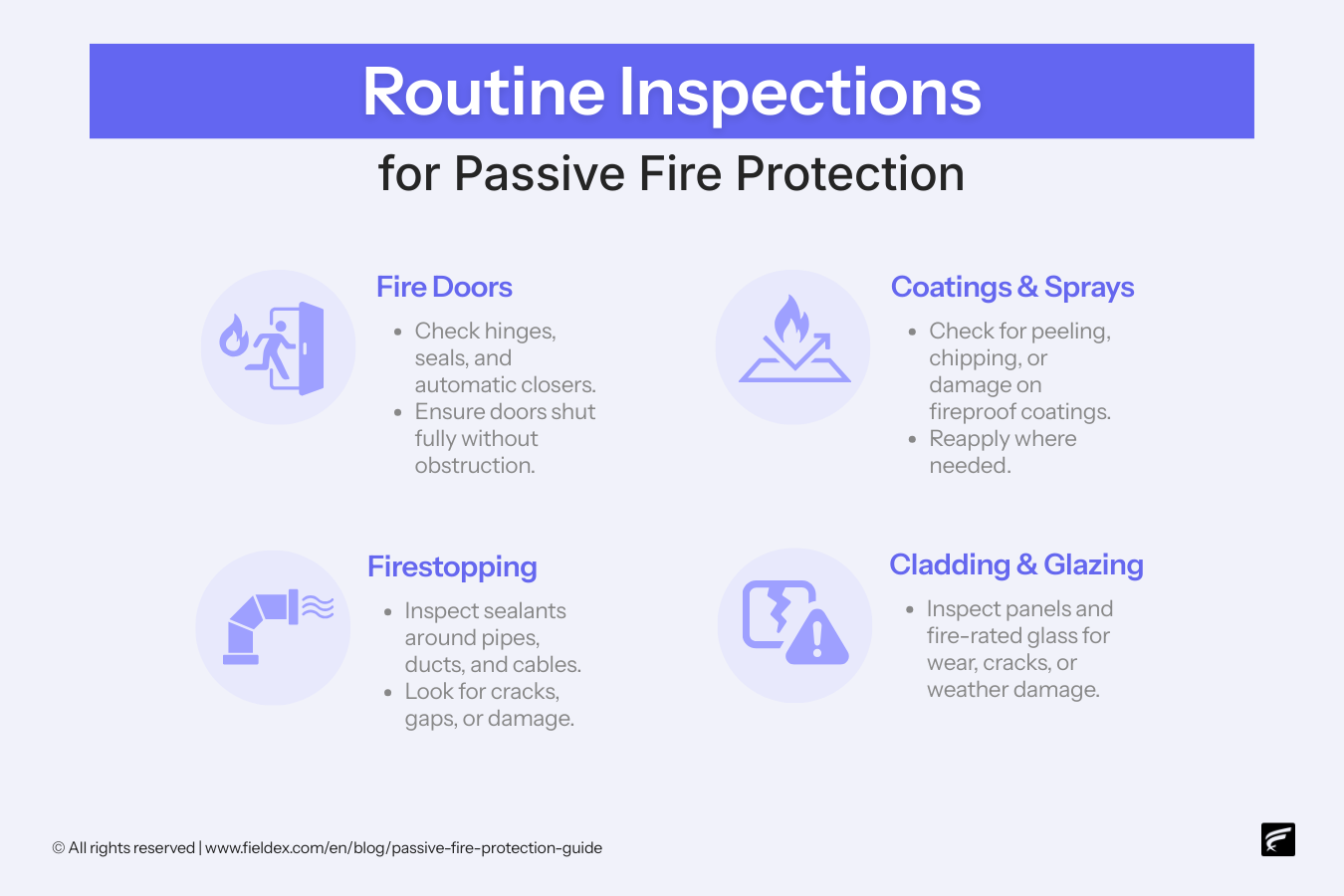

Even passive systems need care. Fire doors get damaged, sealants crack, coatings chip away. Without routine checks, small issues snowball into dangerous vulnerabilities. Remember: PFP is meant to last the lifetime of the building, but only if it’s looked after.

It’s tempting to think, “Eh, that tiny hole around a cable doesn’t matter.” But in reality, smoke – and even flames – can slip through openings less than an inch wide. A fire doesn’t need a grand entrance; it just needs a crack.

Sometimes, fireproofing is left until the end of construction. That usually leads to rushed installs, patchwork fixes, and systems that don’t integrate well with active fire protection. PFP should be baked into the design phase, not slapped on at the finish line.

In short: The biggest mistakes in passive fire protection aren’t usually about the technology; they’re about human shortcuts. Certified materials, proper installation and regular maintenance are non-negotiables if you want these systems to work when it matters most.

Here’s the tricky thing about passive fire protection: because it sits quietly in the background, it’s easy to forget about. Walls don’t beep, coatings don’t flash lights, and doors don’t send you email reminders. But that doesn’t mean they can be ignored. Passive fire protection only works if it’s regularly inspected and maintained.

Even though passive systems aren’t “active,” they still face wear and tear:

Inspections should happen at least annually, but high-risk buildings (like hospitals or factories) often check quarterly.

Authorities don’t just want to hear “Yeah, we check things”. They want proof. Proper documentation includes:

Without records, compliance inspections can get messy, and insurers may push back on claims.

Key standards and codes that guide PFP maintenance:

Missing compliance isn’t just a fine; it could mean shutdown orders or liability in court after an incident.

Managing inspections manually is tough, especially in large facilities with dozens (or hundreds) of fire doors, walls and structural elements. That’s where digital tools like FieldEx make life easier. With FieldEx, fire safety teams can:

Instead of a binder full of checklists (that always seems to go missing when you need it most), everything lives in one place – organized, accessible and audit-ready.

Bottom line: Passive fire protection isn’t “set it and forget it”. It’s “set it, inspect it, document it, and maintain it”. That’s the only way to make sure it works when lives are on the line.

Passive fire protection (PFP) isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Different industries face different risks, so the way PFP is designed and applied can vary widely.

Here’s how it plays out in real-world sectors:

Takeaway: PFP adapts to the environment. Whether it’s a hospital, data center or retail mall, the principles are the same: compartment fire, protect escape routes and keep structures standing. But the execution is tailored to the risks of each industry.

Fire protection may feel like an old unchanging field, but it’s evolving fast. New materials, smarter systems and tougher regulations are shaping the way buildings are designed and maintained. Here’s what’s coming down the line:

The building industry is under pressure to reduce its carbon footprint, and fire protection is no exception. Manufacturers are developing coatings, boards, and insulation that resist fire without relying on toxic chemicals or high-carbon production methods. Expect to see more bio-based and recyclable materials in the next few years.

It’s not just active systems that are getting “smart.” New fire doors and glazing solutions are being designed with IoT sensors that track whether doors are closed, report wear on seals, and even send alerts when a door is blocked. These upgrades make it harder for human error (like propping a fire door open) to compromise safety.

Tragedies like the Grenfell Tower fire have put a spotlight on cladding and passive fire safety worldwide. Regulators are tightening testing protocols, requiring real-world performance testing instead of just lab-based simulations. The result? More reliable products and stricter oversight on what’s allowed in buildings.

With modular construction on the rise, passive fire protection systems are being built off-site and installed as pre-tested, certified components. This reduces installation errors and speeds up compliance checks.

Passive systems may be “silent,” but their inspections don’t have to be manual. Platforms like FieldEx are already making it easier for facility managers to log inspections, track repairs, and stay compliant without drowning in paperwork. The future will see even tighter integration, with PFP components “talking” directly to digital platforms via sensors.

Research shows smoke inhalation causes more fire-related deaths than flames. Expect stronger requirements for smoke curtains, barriers, and compartmentation to keep evacuation routes clear, especially in large public spaces like airports and malls.

The big picture: The future of passive fire protection is smarter, greener and stricter. Buildings won’t just be safer; they’ll be more resilient, sustainable and transparent in how fire safety is monitored and documented.

Passive fire protection isn’t flashy. There are no alarms blaring or sprinklers raining down – it just sits quietly in the background, built into the walls, floors and doors around you. But when fire strikes, that silence becomes its greatest strength. It holds back flames, slows smoke, and keeps escape routes safe long enough for people to get out and firefighters to get in.

From hospitals to high-rises, data centers to shopping malls, PFP is a non-negotiable layer of safety. It saves lives, protects property, and keeps buildings standing when everything else is falling apart.

But here’s the catch: these systems only work if they’re designed properly, installed correctly, and maintained regularly. That’s where many organizations stumble – not with the installation, but with the follow-through.

Digital tools like FieldEx make that part easier. By automating inspections, tracking compliance, and keeping records audit-ready, FieldEx helps fire safety teams focus less on paperwork and more on protecting people.

Passive fire protection may be silent, but it’s never passive. It’s one of the most reliable defenses we have – and with the right tools to maintain it, it will always be ready when it matters most.

Passive fire protection (PFP) is the built-in safety features of a building (eg fire-rated walls, floors, doors, sealants) that stop fire and smoke from spreading. Unlike sprinklers or alarms, PFP works silently in the background, no activation needed.

The safest buildings combine both.

Examples include fire-rated doors, fire-resistant walls and floors, smoke barriers, intumescent coatings on steel, fireproof cladding, and firestopping sealants around pipes and cables.

Because it buys time – time for people to escape, time for firefighters to arrive, and time for buildings to stay standing. Without it, fire spreads faster and evacuation routes fill with smoke.

Common materials include gypsum board, concrete, fire-rated glass, intumescent sealants, spray-applied fire-resistant materials (SFRM), and specialized cladding. Each is chosen based on the building type and risk level.

A fire resistance rating (eg 30, 60, 120 minutes) tells you how long a material or assembly can resist fire before losing integrity. For example, a 60-minute fire door should hold back flames for at least an hour under test conditions.

Yes! Fire doors can get damaged, sealants can crack, coatings can peel, and cladding can degrade. Inspections (often annual or quarterly, depending on local codes) are essential to keep systems effective and compliant.

Usually, it’s the building owner or facility manager’s responsibility to maintain PFP systems. They must schedule inspections, keep records and ensure compliance with codes like NFPA and IBC.

Inspectors look for things like:

Documentation is key; this is where digital platforms like FieldEx help by keeping inspection logs and reports organized.

Yes. Insurance companies often give better rates to buildings with proper PFP systems, since the risk of total loss is lower. Properly maintained PFP also helps avoid disputes over claims after a fire.

.webp)

.avif)